Aeroplane expeditions to Everest

1924 | 1932 | 1933 | 1933-34 | 1951 1960 | Future

1924

Sir Alan Cobham attempted to fly over the mountain. Without oxygen he got nowhere near.

1932

The famous American traveller and writer Richard Halliburton had a go with Meyro Stevens, but in the event his aeroplane failed to climb above 15,500 ft.

1933

The Houston Westland Expedition

The first successful flight over Everest

The early 1930’s was the era when aviation ‘firsts’ were at their most prominent in the public eye. Lindbergh had recently crossed the Atlantic, Byrd had reached the poles, technology was advancing apace and all manner of experimental flights were being done, but still nobody had flown over the highest point on earth.

In

this context, and in the light of indications that both German and French teams

were actively planning flights over Everest, a British team led by Col. Stewart

Blacker was set up. It was supported by

such notables as the famous author and MP John Buchan (39 Steps Etc.) and

funded by Lady Houston, regarded by many at the time as a sort of modern

Boadicea who had also supported the successful 3rd Schneider trophy

challenge in 1931 which had resulted in Britain keeping the trophy. Work on the flight over Everest started in

1932, the objectives, in part, were ‘to

make an important contribution to geography, and to its allied sciences’

and to ‘carry out these feats with purely

British personnel and therefore give a stimulus to enterprise’.

In

this context, and in the light of indications that both German and French teams

were actively planning flights over Everest, a British team led by Col. Stewart

Blacker was set up. It was supported by

such notables as the famous author and MP John Buchan (39 Steps Etc.) and

funded by Lady Houston, regarded by many at the time as a sort of modern

Boadicea who had also supported the successful 3rd Schneider trophy

challenge in 1931 which had resulted in Britain keeping the trophy. Work on the flight over Everest started in

1932, the objectives, in part, were ‘to

make an important contribution to geography, and to its allied sciences’

and to ‘carry out these feats with purely

British personnel and therefore give a stimulus to enterprise’.

Apart from terrific and detailed organization befitting an attempt which was very closely supported by the RAF, the key factor was that Britain possessed some new technology in the form of the supercharged Bristol IS3 Pegasus engine which Flight Lieutenant Uwins, chief test pilot at the RAF experimental establishment, Martlesham had recently used to set a World Altitude record of 43,976 ft in a single-seater aircraft. The expedition chose the unique experimental Westland PV3, later renamed the Houston – Westland, which Uwins recommended as the fastest climbing two seat aircraft the RAF had ever tested. A similar Westland Wallace was chosen as the second aircraft.

Air Commodore Fellowes (uncle of Julian Fellowes the writer, actor and director) was appointed leader of the expedition. After a period of detailed development, particularly the camera equipment, heated clothing and oxygen systems, the two Westlands and tons of support equipment was shipped in early 1933 by sea to Karachi. The Westlands were reassembled at the RAF depot there and flown to Lalbalu airfield, near Purnea in India, some 160 miles SE of Everest. Fellowes, his wife and some other members of the team departed Heston Aerodrome in 3 DH Moths for their own aerial adventure to India, and indeed one of their stops was Catania in Sicily, the home base of Angelo, and they flew across the Mediterranean to Tunisia in the reverse direction to one of the 2004 ‘Over Everest’ team’s earlier flights. It took them just under a month to reach Purnea.

The

Houston-Westland expedition was on-site and ready to go by late March

1933. They did not have to wait

long. The forecast for 3 April was

winds of 67 MPH at 28,000 ft and 58 MPH at 30,000 ft. This was above their stated limits of 40 MPH, but an

early-morning flight to 17,000 ft by

Fellowes in one of the Moths revealed the mountain to be free of cloud so it

was decided to go. The Houston –

Westland was piloted by Lord Clydesdale with Blacker as observer and the

Wallace by David McIntyre with Bonnett as observer. As they approached the mountain at 31,000 ft they realized the

wind had driven them off course and they ended up approaching the mountain from

the leeward side.

The

Houston-Westland expedition was on-site and ready to go by late March

1933. They did not have to wait

long. The forecast for 3 April was

winds of 67 MPH at 28,000 ft and 58 MPH at 30,000 ft. This was above their stated limits of 40 MPH, but an

early-morning flight to 17,000 ft by

Fellowes in one of the Moths revealed the mountain to be free of cloud so it

was decided to go. The Houston –

Westland was piloted by Lord Clydesdale with Blacker as observer and the

Wallace by David McIntyre with Bonnett as observer. As they approached the mountain at 31,000 ft they realized the

wind had driven them off course and they ended up approaching the mountain from

the leeward side.

Clydesdale later wrote in “The Pilot’s book of Everest”:

We were in a tremendous down-rush of air. Though the machine continued to climb, it was climbing in an air current that was carrying it down at much greater velocity. Two thousand feet were lost before the down-rush cushioned itself out on the glacier beds.

We were in a serious position. The great bulk of Everest was towering above us to the left, Makalu down-wind to the right and the connecting range dead ahead, with a hurricane wind doing its best to carry us over and dash us on the knife-edge side of Makalu.

I had the feeling that we were hemmed in on all sides, and that we dare not turn away to gain height afresh. There was plenty of air-space behind us, yet it was impossible to turn back. A turn to the left meant going back into the down-current and the peaks below; a down-turn round to the right would have taken us almost instantly into Makalu at 200 miles per hour.

There was nothing we could do but climb straight ahead and hope to clear the lowest point in the barrier range. . . . With the aircraft heading almost straight into the wind, we crabbed sideways towards the ridge, unable to determine if we were level with it or below.

They eventually scraped over the southern peak by a few feet. Clydesdale would never say how close he came to hitting the mountain other than to admit that it had been “cleared by a more minute margin than he cared to think about, now or ever.”

McIntyre, in the lesser performing aircraft had even worse problems: He could see that if he was to clear the ridge, it would only be by the narrowest of margins:

A fortunate up-current just short of the ridge carried us up by a few feet and we scraped over. The North East ridge appeared to sweep us vertically from our port wing-tips to the summit, and we could see straight down the sheer North side to the glacier cradles at the base of Everest...

As

soon as they passed over the ridge they experienced a considerable ‘air bump’

throwing the aircraft suddenly upwards on the windward side and with their

Pegasus’ at full power they surged over the summit of Everest. Clydesdale would later say that after

experiencing the awfulness of being in the downdraft and only just escaping

collision, entering the updraft was “like

being swept up into heaven.”

As

soon as they passed over the ridge they experienced a considerable ‘air bump’

throwing the aircraft suddenly upwards on the windward side and with their

Pegasus’ at full power they surged over the summit of Everest. Clydesdale would later say that after

experiencing the awfulness of being in the downdraft and only just escaping

collision, entering the updraft was “like

being swept up into heaven.”

In all this excitement, Bonnett trod on his oxygen hose, but had managed to tie a handkerchief around the split in the pipe before he fell completely unconscious to the floor of the observer’s cabin. McIntyre, whilst turning to look at Bonnett, lost the oxygen feed to his mask. In the face of certain disaster if he too fell unconscious, he managed to get it back in place in time, but thereafter had to continually hold it in position with one hand. Heading back to Purnea he lost height as quickly as was safe in the hope that Bonnett was still alive but it wasn’t until they were nearly back at Lalbalu and at about 8,000 ft that to his relief he noticed Bonnett “struggling up from the floor tearing off his mask and headgear. He was a nasty dark green shade but obviously alive and that was enough for the moment.”

Clydesdale spent around 15 minutes circling in the vicinity of Everest so Blacker could take as many photographs as he could. To Blacker it had seemed “like a lifetime from its amazing experiences and yet was all too short”.

Both

aircraft returned safely to Lalbalu to wide British and International acclaim

but the flight had not been a complete success. As Bonnett had been unconscious for half the flight he had been

unable to operate his cameras and after they had been developed it was found

the survey photographs from both aircraft were of little or no use on account

of the dust haze on the day. The film

director wanted more footage too. It

was therefore resolved that a trial flight would be conducted the next day over

Kanchenjunga, some 90 miles to the east of Everest to check all the equipment

was in good working order before a second Everest flight.

Both

aircraft returned safely to Lalbalu to wide British and International acclaim

but the flight had not been a complete success. As Bonnett had been unconscious for half the flight he had been

unable to operate his cameras and after they had been developed it was found

the survey photographs from both aircraft were of little or no use on account

of the dust haze on the day. The film

director wanted more footage too. It

was therefore resolved that a trial flight would be conducted the next day over

Kanchenjunga, some 90 miles to the east of Everest to check all the equipment

was in good working order before a second Everest flight.

Ellison and Bonnett in the Houston-Westland, Fellowes and Fisher in the Westland-Wallace again encountered great turbulence over the peaks, Bonnett felt a bump so great he thought they would be “smashed to pieces” and Fellowes felt it resembled “a rat being shaken vigorously by an expert terrier”. The two aircraft got separated, clouds were everywhere, and Fellowes began to have great trouble with his mask, becoming so hypoxic he couldn’t remember the bearing for the way home apart from “South”. On descending through the haze he picked up a railway line but had no idea where they were, eventually landing by a railway station. Unwilling to stop the engine because the starting handle was back at Lalbalu, they had the greatest difficulty in preventing people from the large crowd which had appeared from getting into the propeller and at the same time finding somebody who could tell them where they were.

In

the meantime the Houston-Westland had returned safely to Lalbalu with no idea

what had become of the other aircraft but that it was last seen disappearing

over the summit of Kanchenjunga. Time

passed with no news and they became increasingly worried that Fellowes had been

forced to make some sort of high altitude emergency landing in what was at that

time totally unexplored territory. Mrs

Fellowes was said to have dealt with the crisis “with firmness and efficiency” while Lord Clydesdale assembled the

food and equipment which could be of use in such an emergency.

In

the meantime the Houston-Westland had returned safely to Lalbalu with no idea

what had become of the other aircraft but that it was last seen disappearing

over the summit of Kanchenjunga. Time

passed with no news and they became increasingly worried that Fellowes had been

forced to make some sort of high altitude emergency landing in what was at that

time totally unexplored territory. Mrs

Fellowes was said to have dealt with the crisis “with firmness and efficiency” while Lord Clydesdale assembled the

food and equipment which could be of use in such an emergency.

Eventually Fellowes discovered he was at Shampur, some considerable distance to the east of Lalbalu, but once they had managed to get enough space for a takeoff and were back in the air and heading home he found they were very short of fuel and was forced to make his second emergency landing of the day “narrowly missing the schoolhouse and some trees” outside Dinjapur, from whence they sent a telegram to Purnea saying they were safe. Fuel and a starting handle were flown to them the next morning in one of the Moths and they later returned safely to Lalbalu.

Whilst they had received nothing but congratulations for the first Everest flight, the near-disasters of this second flight over Kanchenjunga put the prospect of a second Everest flight in the deepest jeopardy. Lady Houston telegraphed “The good spirit of the mountain has been kind to you and brought you success. Be content. Do not tempt the evil spirits of the mountain to bring disaster. Intuition tells me to warn you there is danger if you linger.” And there were other similar messages including one from their insurers who considered their obligation to cover two Himalayan flights complete and refused to cover a second attempt on Everest without the payment of a further £600 premium. As if to reinforce the warnings, the weather had changed for the worse, Fellowes went down with a fever and Gupta, the meteorologist and one of his assistants were severely burned when one of their Hydrogen balloons exploded.

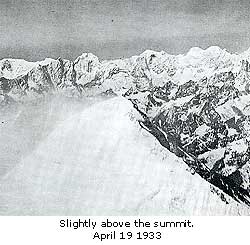

There

was however enough Oxygen for one further attempt. Eventually they got a break in the weather on 19 April. Astonishingly, the four crew, Clydesdale /

Blacker McIntyre / Bonnett planned the whole flight in secret, fearing that if

their leader, Fellowes (who was still in bed) found out he would forbid

it. The forecast was for higher winds

than before so they planned to fly to windward at low level and only climb to

full height at the last minute. So it

was that they approached the mountain at 34,000 ft. at a very slow ground

speed. At 3 ½ miles from Everest

Clydesdale turned East to Makalu, but McIntyre, who felt he had not really had

a proper shot at it the first time because of Bonnett’s oxygen problem, stuck

the headwind out, he later wrote:

There

was however enough Oxygen for one further attempt. Eventually they got a break in the weather on 19 April. Astonishingly, the four crew, Clydesdale /

Blacker McIntyre / Bonnett planned the whole flight in secret, fearing that if

their leader, Fellowes (who was still in bed) found out he would forbid

it. The forecast was for higher winds

than before so they planned to fly to windward at low level and only climb to

full height at the last minute. So it

was that they approached the mountain at 34,000 ft. at a very slow ground

speed. At 3 ½ miles from Everest

Clydesdale turned East to Makalu, but McIntyre, who felt he had not really had

a proper shot at it the first time because of Bonnett’s oxygen problem, stuck

the headwind out, he later wrote:

“There on my right was the enormous

pinnacle, the bright morning sun glinting on the frozen snow and throwing into

strong relief the great rock faces, some of them a sheer 8,000 feet or more.

“There on my right was the enormous

pinnacle, the bright morning sun glinting on the frozen snow and throwing into

strong relief the great rock faces, some of them a sheer 8,000 feet or more.

The next fifteen minutes was a grim struggle. The altimeter showed 34,000 feet. The menacing peak with its enormous plume whirling and streaking away to the South-East at 120 miles an hour appeared to be almost underneath us but refused to get right beneath. After what seemed an interminable time, it disappeared below the nose of the aircraft. I determined to hold the compass course until I gauged we were just over the mountain. Petrol was getting low and I knew there would not be sufficient to go beyond.

We appeared to be stationary. I cast quick, anxious glances behind and below to see if we had passed over. Then suddenly there was a terrific bump—just one terrific impact such as one might receive flying over an explosives factory as it blew up.

It felt as if the wings should break off at the roots, but there was no nasty cracking noise such as would have denoted structural failure. A hurried look round showed every wire taut. There was no sign of slackness anywhere. We were thankful for the marvellous strength of our aeroplane. The bump was a relief in a way, as it indicated the summit and was the signal for a careful, gentle turn to the right to settle down on our predetermined compass course for home.”

When they returned to Lalbalu, Fellowes was furious that they had done the flight without his knowledge and without insurance, but it was mitigated by the fact that they had returned safe and that this time the vertical survey photos were perfect. Under the headline “Success on all points” the Times wrote that “The second flight to Everest, which took place yesterday, may well be described by historians of great achievements as a piece of magnificent insubordination. Made in uninsured aeroplanes and without authority from home it was carried through with the greatest success and has yielded results of the highest scientific value”.

Finally, the Chief of the Air Staff and Marshal of the Royal Air Force, Sir John Salmond sent a telegram on 24 April: “My sincere congratulations on successful completion of difficult survey flight”. This indicated that the Royal Air Force accepted the verdict of The Times.

Bibliography

First over Everest, The Houston-Mount Everest Expedition 1933, P.M.Fellowes and other members of the expedition. First published 1934, reprinted by Pilgrims Publishing, Kathmandu www.pilgrimsbooks.com

Roof of the World. Man’s first flight over Everest. James Douglas-Hamilton, Mainstream publishing, 1983.

1933 - 1934

With

practically no flying experience Maurice Wilson "the mad

Yorkshireman", flew a DH Gypsy Moth named ‘Ever-wrest’ to India in

1933. He said that he did not intend to

fly over Everest but would fly as high as the machine would go, crash it on the

mountainside, and proceed to the summit on foot. "I’ve been

studying the mountain, I've spent two months in an aeroplane, I want to show

that long training for flying is not necessary. When I have accomplished my little work, I

shall be somebody. People will listen to me." He took with

him a silken Union Jack to plant on the summit.

With

practically no flying experience Maurice Wilson "the mad

Yorkshireman", flew a DH Gypsy Moth named ‘Ever-wrest’ to India in

1933. He said that he did not intend to

fly over Everest but would fly as high as the machine would go, crash it on the

mountainside, and proceed to the summit on foot. "I’ve been

studying the mountain, I've spent two months in an aeroplane, I want to show

that long training for flying is not necessary. When I have accomplished my little work, I

shall be somebody. People will listen to me." He took with

him a silken Union Jack to plant on the summit.

"Everest

Airman Missing" said the headlines in May 1933 but in fact he was probably

under arrest in Karachi for having flown the whole way from England with

practically no paperwork. He then seems

to have spent a year or so in Darjeeling living with Indian Mystics “mastering

the Science of Yogism, subordinating the body to the will of the spirit until

he could live for days without food, and endure cold and hardship sufficient to

kill an ordinary man.” Having sold

his aircraft he set out with three guides to walk the 300 miles to the foot of

Everest and then climb it solo. It

would seem he was last seen alive setting out alone up a glacier equipped with

a tent, three loaves, two tins of oatmeal, a camera, and his silken Union Jack.

"Everest

Airman Missing" said the headlines in May 1933 but in fact he was probably

under arrest in Karachi for having flown the whole way from England with

practically no paperwork. He then seems

to have spent a year or so in Darjeeling living with Indian Mystics “mastering

the Science of Yogism, subordinating the body to the will of the spirit until

he could live for days without food, and endure cold and hardship sufficient to

kill an ordinary man.” Having sold

his aircraft he set out with three guides to walk the 300 miles to the foot of

Everest and then climb it solo. It

would seem he was last seen alive setting out alone up a glacier equipped with

a tent, three loaves, two tins of oatmeal, a camera, and his silken Union Jack.

Wilson’s body was found by the Shipton expedition 21,000 feet up on the East Rongbuk Glacier on 9 July 1934. His last diary entry of 31 May 1934 said: "Off again, gorgeous day." He was buried in a crevasse and Shipton built a cairn to mark the spot. It is just below the normal location of Advance base camp.

In a final twist in the tale, the 1960 Chinese expedition found a previously unknown ‘old tent’ at 8,500 meters, higher than any other one known at the time and far above the North Col. There has been recent speculation that this “Mystery Tent” near the top of Everest could possibly have been Wilson’s, though another candidate is a 1952 Soviet expedition which, in keeping with the cold-war one-upmanship of the time was kept secret from the World after they failed to summit.

1951

British pilot John Jordan attempted to fly over Everest in a Stearman biplane. He failed to get higher than 23,000 ft and got frostbite.

1960

Pilatus PC-6 Porters, a Swiss STOL aircraft with excellent high altitude performance started to appear in Nepal. One of the most famous Porter pilots was Emil Wick who made many flights around and reputedly over Everest.

Future projects

Any

attempt to recreate the Houston-Westland flight involves the building of a

replica aircraft because there are simply no Westland Wallaces left in existence,

though there is an original fuselage in the RAF museum, Hendon. George Almond’s Wings Over Everest

project aims to build a replica Westland Wallace and then fly it over Everest

in an expedition led by Rebecca Stephens MBE, The first British woman to climb

Everest and the Seven Summits. Some

work has been completed on the aircraft, but the project is apparently on hold

at the moment for want of funds.

Any

attempt to recreate the Houston-Westland flight involves the building of a

replica aircraft because there are simply no Westland Wallaces left in existence,

though there is an original fuselage in the RAF museum, Hendon. George Almond’s Wings Over Everest

project aims to build a replica Westland Wallace and then fly it over Everest

in an expedition led by Rebecca Stephens MBE, The first British woman to climb

Everest and the Seven Summits. Some

work has been completed on the aircraft, but the project is apparently on hold

at the moment for want of funds.