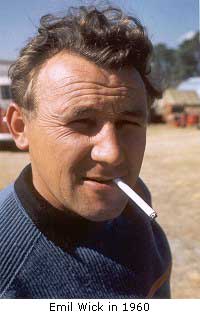

Emil Wick

The Swiss pilot Emil Wick became something of a legend in his own lifetime, both for his outrageous sense of humour and his extraordinary exploits whilst flying Pilatus Porters in the high Himalayas. He holds the record for the highest landing and takeoff ever made and developed the art of soaring the Lhotse face of the Western Cwm adjoining Everest.

His

first visit to Nepal was in 1960 in support of a Swiss/Austrian/Polish

expedition led by Max Eiselin to climb Dhaulagiri in central Nepal, one of the

last remaining unconquered 8000m peaks.

Until this time this mountain had proved very difficult to crack because

of the long approach so they decided to try air support.

His

first visit to Nepal was in 1960 in support of a Swiss/Austrian/Polish

expedition led by Max Eiselin to climb Dhaulagiri in central Nepal, one of the

last remaining unconquered 8000m peaks.

Until this time this mountain had proved very difficult to crack because

of the long approach so they decided to try air support.

The Swiss aircraft manufacturer Pilatus had just developed a new STOL aircraft, the PC-6 Porter and additionally they had some experience of landing on glaciers starting in November 1946 when the pilots of an American DC3 plane with 12 passengers flying over the Alps lost orientation in bad weather and landed unknowingly in deep powder snow on the Ghauli Glacier at an altitude of 2800 m. beside the Wetterhorn in the Bernese Oberland. The DC3 is still there in the glacier and waits to reappear at the lower end some day but everybody was rescued by a Swiss Army light aircraft equipped with skis.

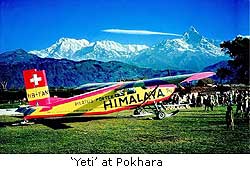

The prototype Pilatus PC-6 Porter named “Yeti” was flown out to Nepal by Ernst Saxer and Emil Wick not without incident. Nobody had ever heard of this new aircraft and in Damascus, Syria the tower had understood DC-6 and they had prepared for the arrival with a large passenger stairway and a string of luggage trucks and were somewhat surprised when the tiny Yeti arrived.

At that time Nepal's hinterland was very much off limits to foreigners, passengers on domestic flights had to have their passports stamped, and planes were supposed to carry liaison officers but Emil wasn't much troubled by them: "I'd make a few bumps and the Liaison officers were not so happy about flying any more. Many days I flew alone."

Pokhara

was chosen as the base airfield, although there was no petrol available, it had

to be flown in from Bhairava. Reconnaissance flights around Dhaulagiri revealed

two possible landing places, one at the foot of the NE spur at 5700 m and a

lower one at 5200 m on the Dambush pass, both a bit higher than hoped. A landing at either would be a World record

(which stood at 4200m at the time) and right at the limits of even this capable

aircraft.

Pokhara

was chosen as the base airfield, although there was no petrol available, it had

to be flown in from Bhairava. Reconnaissance flights around Dhaulagiri revealed

two possible landing places, one at the foot of the NE spur at 5700 m and a

lower one at 5200 m on the Dambush pass, both a bit higher than hoped. A landing at either would be a World record

(which stood at 4200m at the time) and right at the limits of even this capable

aircraft.

Flights ferrying expedition supplies onto the mountain from Pokhara started on March 29th, 2-3 flights full of cargo were flown on an average morning before it clouded over. Yeti’s landings at 5700m are still in the Guinness book of records as the highest made by any fixed wing aircraft. There was a return load also. "We were staying in Pokhara, but there was no electricity .So we always carried a big drum up to the glacier, filled it with snow, flew it to Pokhara and cooled our beer."

At

one stage they had serious engine problems and had to send for a new 350Hp

Lycoming from Switzerland. With no radio

contact, the climbing team were unaware of what had happened but stuck it out

despite the fact that their food deliveries were not complete and were forced to live on very

monotonous meals of oat flakes and rice. After 3 weeks and something of

a logistical miracle Yeti was back in the air and supplying the

expedition.

At

one stage they had serious engine problems and had to send for a new 350Hp

Lycoming from Switzerland. With no radio

contact, the climbing team were unaware of what had happened but stuck it out

despite the fact that their food deliveries were not complete and were forced to live on very

monotonous meals of oat flakes and rice. After 3 weeks and something of

a logistical miracle Yeti was back in the air and supplying the

expedition.

Eventually, on May 5, they crashed on take off at the Dambush pass after the rubber grip of the control column broke off. Saxer and Wick were uninjured but in serious jeopardy because they were not acclimatized to the altitude. They managed to walk to the Dambush camp, and the next day down to Tukucha (2650 m). The remains of the plane are still there, several hundred meters below the Dambush pass. The Porter Vintage Association has an ambition to recover and rebuild it.

Overall the expedition was a success however. Six mountaineers summited Dhaulagiri on 13 May followed by a further two 10 days later.

By the early 1970’s most Porters were fitted with the much more powerful P&W PT6 gas turbine giving them their very distinctive long nose. As a factory pilot Emil Wick had logged thousands of hours on Porters including some time spent in Africa and some long delivery flights to Australia. In 1972 he was seconded to Royal Nepal Airlines as a training captain.

One of his earliest exploits was back on Dhaulagiri, to airdrop supplies to the 1973 US expedition. Amongst the normal stuff he dropped two bottles of wine and a live chicken. The Sherpas would not allow the Chicken to be killed on the mountain, so it became the expedition pet. It was carried, snow-blind and crippled with frostbitten feet to Marpha, where it finally ended up in the cooking pot.

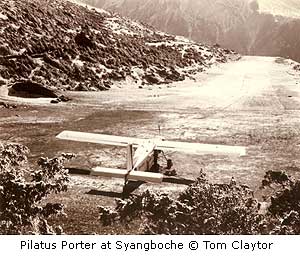

In

his 12 years with Royal Nepal Airlines Emil Wick is reputed to have made more

than 1000 landings at Syangboche airstrip just above Namche Bazaar in the Solu

Khumbu valley on the well trodden route to Everest Base Camp. At 12,500ft it is

the highest regularly used airstrip in the world, about 400m long with a

mountain at one end and a ravine at the other.

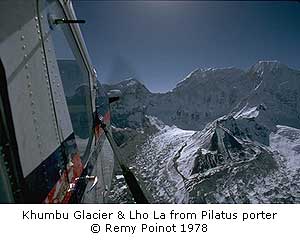

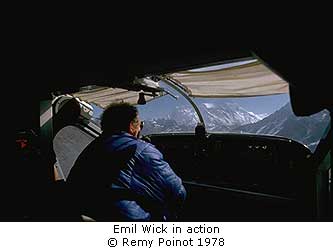

The French photographer Remy Poinot

flew with him from there for an article in Flieger Magazin in 1978:

In

his 12 years with Royal Nepal Airlines Emil Wick is reputed to have made more

than 1000 landings at Syangboche airstrip just above Namche Bazaar in the Solu

Khumbu valley on the well trodden route to Everest Base Camp. At 12,500ft it is

the highest regularly used airstrip in the world, about 400m long with a

mountain at one end and a ravine at the other.

The French photographer Remy Poinot

flew with him from there for an article in Flieger Magazin in 1978:

In the mountain we stayed at the Everest View Hotel for wealthy Japanese tourist and I remember there was oxygen tank and mask in every room. We didn't had to use it but we felt the thinnest of air, carrying around the heavy camera bag was quite difficult.

I remember Emil Wick was VERY concerned about very sudden atmospherical conditions changes. Of course there was not only no reliable weather forecast but no forecast at all, and the Pilatus radio didn't work while on the ground in high altitude landing field due to the shadow of the mountains, and barely when flying too (Emil was much more confident in himself).

Emil

kept looking at the sky, even by what seemed a clear weather for us, he was

afraid the clouds could close very fast soon after take off and we could not

land, so we kept waiting and waiting until he was absolutely sure we can fly.

The winds too can gain speed or change course in no time and that was one of

his constant concern even with the power of the Pratt & Whitney engine.

Emil

kept looking at the sky, even by what seemed a clear weather for us, he was

afraid the clouds could close very fast soon after take off and we could not

land, so we kept waiting and waiting until he was absolutely sure we can fly.

The winds too can gain speed or change course in no time and that was one of

his constant concern even with the power of the Pratt & Whitney engine.

At around this time he developed the art of ‘flying into the hole’, otherwise known as the Western Cwm. He was apparently the only pilot permitted to do this, and he discovered that in the right conditions it was possible to soar the Porter up the Lhotse face to an altitude considerably in excess of the normal ceiling of the machine.

Ron Faux went on one such flight:

When I was a journalist on The Times covering the 1978 Austrian expedition to Everest, on which Reinhold Messner and Peter Habeler planned an “oxygen free” attempt on the mountain, I flew in the Pilatus Porter with Emil Wick from Syangboche airstrip. The plane was normally used for ambulance flights, expedition support, search and rescue and for ferrying very rich Americans and Japanese direct from Kathmandu to the Everest View Hotel (EVH) above Syangboche. Since there seemed a correlation between age and wealth, the only clients with funds enough for the flight were knocking on in years. Many discovered that projecting an aged frame from four thousand to fourteen thousand feet in a short space of time led to inexorable problems. Maybe some were following a “See Everest and die” maxim because some did, or were returned to Kathmandu unconscious.

Wick

strapped us into the aircraft, gave everyone an oxygen mask and placed a

cushion on his seat. He was of short stature and without elevation from a

cushion, what lay beyond the instrument panel was a mystery to him. I remember

his very positive, cheerful and enormously self-confident manner. He was, I was

told, the only pilot the Nepalese authorities would allow to fly “into the

hole” as he called the Western Cwm.

Wick

strapped us into the aircraft, gave everyone an oxygen mask and placed a

cushion on his seat. He was of short stature and without elevation from a

cushion, what lay beyond the instrument panel was a mystery to him. I remember

his very positive, cheerful and enormously self-confident manner. He was, I was

told, the only pilot the Nepalese authorities would allow to fly “into the

hole” as he called the Western Cwm.

We first flew towards Nuptse and skirting the northern edge of the ridge, tracked the edge of the Cwm towards Lhotse, swinging left about level with the South Col. The air was completely still and I was not aware of any turbulence. Wick announced that we were unable to fly beyond the South Col for fear of a Chinese missile and that reaching summit level was not possible on that particular day because the pressure was too low and the air insufficiently dense. The single turbo-prop engine “same as on a Viscount” did not have the grunt to go higher that day. Instead we flew close to the south-west face of Everest, perhaps 400 metres away from it, and I had a close-up view of the route that Bonington and Co had climbed three years previously.

Wick

then flew the aircraft above the Lhotse face and said: “OK, we dive the

bastard” and yanked the controls into a spiral dive. I wasn’t a qualified pilot

at the time but it did seem he had to use maximum input on the controls to make

the Porter do anything. We then swooped down the Lhotse face over the heads of

two Austrians climbing towards the South Col. They could not have been best

pleased after spending two months manoeuvring themselves into a position of

Biblical loneliness and danger when out of the sky plunges an aircraft whose

wheels almost took their hats off. If the noise and shock wave alone did not terrify

them the subsequent risk of avalanche on a 50 degree snow and ice slope would.

Wick

then flew the aircraft above the Lhotse face and said: “OK, we dive the

bastard” and yanked the controls into a spiral dive. I wasn’t a qualified pilot

at the time but it did seem he had to use maximum input on the controls to make

the Porter do anything. We then swooped down the Lhotse face over the heads of

two Austrians climbing towards the South Col. They could not have been best

pleased after spending two months manoeuvring themselves into a position of

Biblical loneliness and danger when out of the sky plunges an aircraft whose

wheels almost took their hats off. If the noise and shock wave alone did not terrify

them the subsequent risk of avalanche on a 50 degree snow and ice slope would.

Down the Cwm we plunged perhaps 150ft above the surface and over the lip of the Kumbu icefall and the startled upturned faces at base camp. Whilst Wick was clearly master of his element and enjoying every second, his passengers were too stunned to speak. Over base camp and down the valley to Syangboche, renowned for its turbulence, but the air remained perfectly smooth.

Interesting to note that Reinhold Messner insisted that he make the flight without wearing an oxygen mask. He was well acclimatised and manifestly had lungs that reached his knees but even so he turned a curious shade of blue, his eyes crossed and lost some of their focus but, according to him, he remained fully conscious. As history records, he and Habeler did reach the top, unmasked.

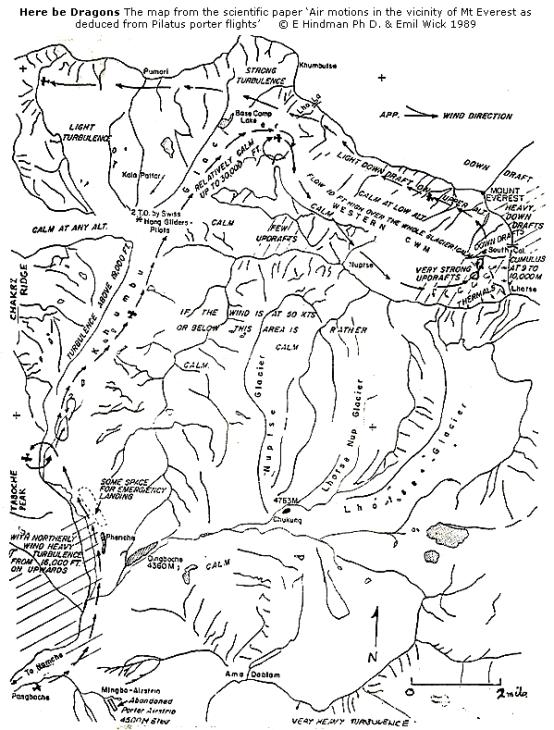

Emil

Wick retired from the job in Nepal in 1986 aged 60. In 1989 he co-wrote with Professor Edward E. Hindman of the City

College, NY, USA, a scientific meteorological paper entitled “Air motions in

the vicinity of Mount Everest as deduced from Pilatus Porter flights” which

gives a fascinating insight into his vast experience of flying in the Everest

region. Notably, this paper contains an

extraordinary ‘Here be dragons’ map showing the areas around Mt Everest where

lift, sink and turbulence may normally be encountered. Professor Hindman has written various other

papers on the subject over the years as his ultimate ambition is to fly over

Everest in a sailplane.

Emil

Wick retired from the job in Nepal in 1986 aged 60. In 1989 he co-wrote with Professor Edward E. Hindman of the City

College, NY, USA, a scientific meteorological paper entitled “Air motions in

the vicinity of Mount Everest as deduced from Pilatus Porter flights” which

gives a fascinating insight into his vast experience of flying in the Everest

region. Notably, this paper contains an

extraordinary ‘Here be dragons’ map showing the areas around Mt Everest where

lift, sink and turbulence may normally be encountered. Professor Hindman has written various other

papers on the subject over the years as his ultimate ambition is to fly over

Everest in a sailplane.

Emil Wick died on September 27, 2000 aged 74 in Geneva, Switzerland.

Sources

Various websites, including summitpost.com and Porter Vintage Association

Ronald Faux

Professor E. E. Hindman

Technical Soaring Magazine