News release: 24 Apr, Darwin | |

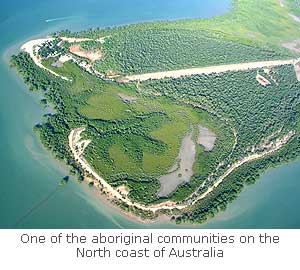

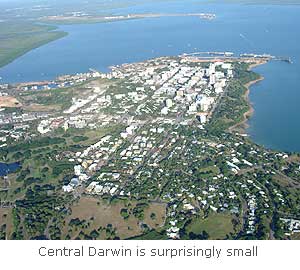

| Well, after a gruelling thirteen and a half hours flying we've got here from Kupang. I've drunk a number of cold beers, a considerable number in fact, and all is well with the World. Jon left Kupang for Darwin at midday so I was up early finishing the machine off so he could take more-or-less everything with him except the clothes Miles and I are standing in. Most of the afternoon I spent with Bagus doing what seemed to be an almost Indian quantity of paperwork but we managed to get everything done including Customs and Immigration who are only in the airport when the twice-weekly flight to Darwin comes. They seemed perfectly happy to post-date the stamps in our passports even though I still didn't really know whether we were going tomorrow. I filed my flight plan with Darwin as the destination but with Truscott and Wyndham as first and second alternates. It's so difficult to get the machine out of its shed we decided to leave refuelling to the morning when it's out on the apron; we went to see the fuel people to make sure they would be about at dawn. Very early next morning I called the met at Darwin. With the proviso that there was a mild mid-level trough somewhere between Indonesia and Australia but basically the whole Timor sea was clear, the girl there gave me the following wind forecast: 3000 ft 110 deg 10 Kt A straight line to Darwin is 109 deg and to Truscott 147 deg. On the basis that with our extra 40 litres we now have an endurance of 7 1/2 or maybe 8 hours, then if we were to go at all, it wasn't a very difficult decision to decide where to go to, but for the sake of completeness, at our normal air speed of 65 Kt this forecast works out to: Darwin; 446 Nm Truscott; 283 Nm Of course Truscott was the obvious choice. She also said that the wind was likely to reduce the following day which would be good because by going to Truscott we would be doing two sides of the triangle and the Truscott to Darwin leg is North-east and therefore dead into the prevailing wind, but the way I was intending to do it, at least mostly over land. Our taxi had to stop twice on the five mile run to the airport to get air in one if its tyres. You don't do this at garages as there aren't any, but at kiosks by the side of the road which will also sell you litre bottles of petrol. It was just getting light as I extracted the machine from its shed, somehow it was a bit easier getting it out than it had been getting it in. I remembered to screw the radio antenna back on the kingpost and manoeuvred it through the trees behind the fire station so I could taxi round to the apron to fill it with fuel. Needless to say there was no sign of the fuel people, Bagus went off to find them, it was an hour or so before they turned up making excuses about how they had to check the quality or something. My guess was they were late out of bed. Their filler hose wouldn't fit in the pannier tanks so avgas was squirted quite liberally over the machine while we filled it. With the risk that a spark from the pump might set it all off I made sure the new plumbing actually worked. It did. The final problem was paying for it. I thought they'd said the day before that Rupiah would be OK, but it wasn't; you must pay in USD, and of course the few I had left all had the wrong serial numbers. At this moment of stalemate one of Bagus' mates produced two one hundred dollar bills with acceptable serial numbers which he was prepared to swap for my unacceptable ones and our problem was solved. It was getting a little bit windy by this time. We were heavier than we've ever been and as we took off I was slightly worried how the machine would perform in the first few miles over land where it was likely to be turbulent, but it seemed to be the same as usual and it wasn't that turbulent anyway. It was also a bit cooler than usual so there was no need for Miles to lift up the pannier to keep the oil temperature down. The GPS was showing under 40 Kts on the ground and 8 and something hours to Truscott which was a bit worrying, the wind was stronger than forecast, but once out over the coast and above about 6000 ft it improved to just over 40 and about 6 hours which was reasonably comfortable so long as the wind didn't change. At our sort of speed over this distance the difference of only a few miles an hour makes an enormous difference in flight time. Twice I told kupang on the radio that we were going to Truscott, NOT Darwin. Even after the second call I wasn't convinced they appreciated we were going in quite a different direction than heading to Darwin direct which could be a problem if we didn't turn up anywhere in Australia and someone had to come looking for us. Oh well, there's always the beacon attached to my lifejacket; it's rather a good one, you rip the cover off and a metal antenna coiled like a tape measure pops out. It starts transmitting on 406 MHz which is received by satellites and 121.5 MHz which is the standard aviation distress frequency. Once the internal GPS finds itself this information is added to what's sent to satellites and theoretically can pinpoint you to 200 ft. I have no desire to try it out. We kept climbing gradually to about 8000 ft, ground speed was around the mid 40's and for no discernable reason the air was quite lumpy, perhaps something to do with that trough the forecaster mentioned. It was also quite cold so Miles suggested we try going much lower as the forecast suggested lower winds there, but descending below 4000 ft we were back down to the low 40's so we started a gentle climb back to about 9,000 ft where things improved to the high forties and eventually the low fifties. Until about 50 miles out there were a few small boats about, then one big ship, and then nothing until we came across the Jabiru oilfield about half way. This mystified me a bit as I've never seen anything quite like it, it's a floating platform tied with a huge A frame to a big post known as a Single Anchor Leg Rigid Arm Mooring (SALRAM). About ten miles away there was what looked like a tanker tied to another post which I assumed was collecting oil from the platform via an undersea pipeline. The helicopter platform would be far too small but one side of the deck looked clear, I wondered if I would be able to land on it or whether it would be better to just land in the sea nearby, but would anyone see us? I couldn't see any movement apart from water gushing from a pipe out one side and a gas flare on top of a tall mast; I didn't even know if it was manned at all, though I assumed there would be someone on the ship being loaded. Our engine hummed away as usual. I didn't tell Miles about the platform until it had receded into the distance. He likes taking photos of things even though quite a lot of them either aren't pointing in the right direction or he's got his hand over the lens. Some are quite good though, but I live in constant terror of him dropping a glove or the camera or something else into the prop whilst he's fiddling around taking them. By waving his arms about the engine makes a different noise too as the air is disturbed going into the prop. In the middle of the sea any change of noise is always a bit alarming. Because of this I tend to stay rather still. On this second half of the flight, still at 9,000 ft or so, the air settled down a bit, we must have been past the trough though there had been no sign of any clouds anywhere. It was quite cold and Miles was shivering in the back but he agreed it was better than going more slowly lower down where it would be warmer. We passed a couple more ships making their way from right to left up the Timor Sea, perhaps to Darwin, but even as we neared the coast there was no sign of any small boats at all. I managed to get in touch with Brisbane centre about sixty miles out. Brisbane seemed an awfully long way away but it seems they control all the airspace to the north of Australia via a series of repeaters. Eventually some clouds did appear on the horizon which I assumed might be over land. My first sight of land though was Troughton Island. This is where Brian came to in his Shadow twenty years ago. At that time it was an important supply base for the off shore oil installations. Of course those were the days before GPS so Brian was using 'traditional' methods of navigation. He told me that he was getting low on fuel and wasn't actually going quite in the right direction to get there, but more than by luck than anything was found by a helicopter out at sea and redirected a bit towards the island, otherwise he might have taken his machine for a swim a second time. (He'd discovered it floated quite well earlier in the journey off Qatar). Nevertheless, Troughton is such a tiny postage stamp of a place you've got to admire the man for getting there at all. Eve Jackson was of course the first person to fly from London to Australia a couple of years before Brian, also in a CFM Shadow. I must ask her which route she took across here. These days all the oilfield helicopter operations have been moved to Truscott on the mainland but I'm told Troughton is still manned by a couple who do a month on and a month off to maintain it for emergency diversions, must be a pretty lonely life. Twenty miles further on, Truscott hove into sight and I throttled back into a gentle descent. Miles asked why I sometimes descended like this by reducing throttle and sometimes by putting the trim on full fast. I didn't know really, it's random, or how I'm feeling, or something. I switched the radio over to Truscott CTAF on 128.0 which was a 'Common Traffic Advisory Frequency', I supposed a sort of area unicom but just got loads of noise like someone was permanently transmitting. On the approach I noticed what looked like dispersal areas in the bush either side of the strip and it turns out that Mangalalu Truscott, to give its full name, was built in 1944 by the Royal Australian Air Force as part of their defence against the Japanese. It was named after Squadron Leader Keith 'Bluey' Truscott who was a pre-war 'Aussie rules' star and Australia's leading air ace of 1943. Through sheer boredom, he and Flying Officer Ian Louden decided to practice combat attacks on a Catalina they were escorting home from a long range mission in their Kittyhawk A29-150's. On one attack he passed underneath the Catalina but it would appear he'd failed to notice how low he was and at 1735 on 28 March 1943 slammed into the gulf of Exmouth and was killed. Originally the airfield was a temporary affair made of perforated steel planking (Marsden matting). It more or less fell into disuse after the war but has recently been resurfaced and lengthened to accommodate Australia Customs Service planes on the look out for boat people and illegal fishermen. There were looks of complete bemusement on the faces of the people there when we arrived, it's such a remote place people don't usually just 'arrive' like we had just done. When Miles asked why his mobile phone wasn't working the reply was along the lines of "no mobiles here mate, we're way too far out in the boonies". It was great to be in Australia at last. As soon as they'd got over their surprise we were made incredibly welcome. The airfield is operated by ShoreAir but mostly used by CHC for their helicopter operations out in the Timor sea. It turns out that what I'd seen out there wasn't quite what I'd thought it was. The ship I thought was filling up from a buoy was actually the Jabiru Venture FPSO, Australia's first Floating Production, Storage and Offloading vessel and it's there permanently, though after 20 years it's coming to the end of its useful life. The smaller one we flew directly over was the Challis Venture FPSO. Crude oil is produced and stored in these FPSOs and exported from time to time by shuttle tankers. Jabiru didn't look that big to me, but it is a 140,000 ton ship, even Challis, 'the small one' is over 100,000 tons. That made me wonder what size those tankers I saw in the Gulf and Singapore must have been, because they did look big. Each has a crew of about thirty people who do two weeks on and two weeks off, which, along with other Timor platforms such as Scott Reef, Skua and Buffalo keeps CHC's two Super Pumas constantly in work. "It's lucky you weren't here two weeks ago", said Greg Meakins, CHC's most senior pilot at Truscott, "that was the last of the wet, and it's been very wet this year. We have to evacuate all the platforms whenever a tropical cyclone comes through, and we had three of them in March including George which was a cat 4 storm, the biggest one we've had since Tracy flattened Darwin in '74. Boy, did it rain here!" He was talking waterfalls rather than mere 'rain', the highest recorded rainfall at Truscott was January 1998 when they had 38 inches in a 72 hour period. The base manager rang the Australian Customs helpline to tell them we were here. The person who answered was in Melbourne and had no idea where Truscott was, "Queensland, is it?" he asked. "No, Western Australia", I said; only a thousand or so miles off the mark. There followed a number of calls back from nearer and nearer, from Perth, then Port Hedland, and finally Darwin where we planned to actually enter Australia formally. They all seemed quite calm as there was no real chance of us disappearing illegally as there's no road to Truscott; everything comes in by barge or air. I had the number for the immigration people in Darwin so I rang them and they seemed equally calm. There was plenty of avgas at Truscott and our lack of Australian money wasn't a problem either, just pay at our office in Darwin, they said. Space was found in front of one of the Super Pumas in the hangar, though I had to promise to be out at 4 in the morning which is when they start getting things ready for the day. I got talking to Greg about how one does things in Australia in terms of flight plans and things. Mostly it's all done online and I was provided with a vast amount of Notams and met info for our route to Darwin. They recommended I went via Kununurra rather than Wyndham as we were much more likely to find fuel there. Seemed good to me so that's what I put in my online flight plan. I told him about the permanent transmission I'd been receiving on approach, he tried it in one of the helicopters but it all seemed OK. We supposed I was getting it from somewhere else like Kalimburu which isn't far away. I didn't have any map at all beyond Darwin but I supposed the best thing to do would be to fly down the road towards Brisbane and then down the east coast to Sydney where there was likely to be less afternoon turbulence than if we went further inland. The prevailing wind is south-easterly, he said, it's going to take a while. Greg told me the maps I would need in Australia are known as WAC's and are 1 million scale, the same as the ONC's I've been using up until now. For Brisbane and Sydney I would also need VTC's, Visual Terminal Charts for the relatively complicated airspace there. The main problem with all these was that he thought it was unlikely I would be able to get any of them in Darwin, "we usually get them by mail order" he said, "you could try the flying club at Darwin, but it's pretty small. Maybe I've got some." he said, and rang his wife Dot in Darwin to see if she could dig out any old maps from his office at home which I could go and collect once we got there. There was no time for mail order, of course, but I was fairly sure I'd find them somewhere as we went along. After an excellent dinner in the Canteen - Miles' first meal of something other than Peppercorn steak and salad for something more than 2 weeks, Greg showed us over one of the Super Pumas. Once Miles was installed in the driver's seat Greg pushed some buttons and said "and this is the engine starting", and a bit louder, over the big whirring noise of 2000 horses coming to life: "it's a completely automatic sequence from now on", but he shut it down before the rotor bashed the inside wall of the hangar. Miles was very excited. Although these are 20 year old machines they're the standard bit of kit for oilfield work all over the World, "not very efficient by modern standards, but very robust if you look after them properly". I was impressed by some of the gadgetry; they've a satellite link which permanently transmits the thing's position and an outline of its mechanical status. (Why didn't we have one of those? It's not so difficult to transmit position these days and would have provided an interesting nearly-live update on where we were - I suppose it was yet another thing you-know-who didn't think of.) It also has a very sophisticated systems monitoring system which is downloaded after every flight, every conceivable thing like gear box temperatures, vibrations and lots of other things are recorded, there's even a sort of optical device in the nose which looks at the main rotor to check each blade is tracking properly. The only other big helicopters like this I've been in are those Mi-17's they had in Nepal, I said the main rotor on them seemed so out of balance it was a bit like riding a horse and the windscreen was so opaque you couldn't see a lot; "hmm... that's the Russians for you" was the reply. The apron was a blaze of lights when I got there at 4 the next morning and just before dawn two medium sized planes arrived with platform workers. They start early because mostly these people come from elsewhere in Australia besides Darwin and they need to get out to the rigs and back with the departing crews in time to get them to Darwin to catch the midday flights to wherever they live. After a full on English breakfast in the canteen which was guaranteed to solve even Miles' demands for early morning 'carbs', we set off for Kununurra just after dawn. Not long after takeoff we passed over the dirt strip at Kalumburu which, as the Drysdale River Mission was attacked in 1943 by 21 Japanese Kawasaki Ki-48 'Lily' bombers from Kupang. Mission Superior Father Thomas Gil was among several civilians killed and many buildings were destroyed or severely damaged during the raid. Thereafter it was what Brian likes to call the GBA 'the great bugger-all', there were a few small rivers and streams with water still in them from the 'wet' but mostly just miles and miles of rocky bush covered terrain with very few places one could make a successful landing. It's difficult to imagine the Japanese really thought they could successfully invade a place as vast and barren as this part of Australia but the prospect was taken very seriously at the time and the Drysdale River Mission attack was one of the main reasons why Truscott was constructed. I was pleasantly surprised by the lack of turbulence; it was so calm Miles went to sleep for quite a while. The radio was doing the same thing on 128.0 and picking up a lot of what must have only been my engine noise but it seemed to be very specific on that one frequency and was fine on any other. As soon as we got some height I could talk to Brisbane Centre again. Eventually we came to some big mud flats of the Cambridge Gulf which leads up to Wyndham. I could just see the airfield off to the right, some distance from the town. I was glad we weren't going there as I imagined it could take some time for someone to come with fuel. I was on the look-out for salties but we were too high to see anything. They said there's a 6 metre one down by Truscott's barge pier; now that's a BIG crocodile. There were even some at Troughton though it's such a small and barren place nobody could think what they could possibly have lived on. The best advice on how to deal with them seemed to be to always be aware they might be there, most people get eaten when they go paddling or swimming without thinking. Nobody could advise me on the best strategy to adopt if one actually encountered one; run away, I thought might be the best bet. Over a small ridge from the mud flats and I could see Kununurra airfield, very unexpectedly surrounded by intensively cultivated fields. I supposed there must be some sort of very good all year supply of water for irrigation. I landed and parked on a rather nice lawn in front of the terminal building, but was soon chased off, not because there was a 'do not park on the grass' sign or anything, but because the daily jet was soon arriving and they were afraid our machine might get blown away. It was a surprisingly busy little airport with light and small regional aircraft coming and going all the time. There was no ATC and practically no wind so people seemed to be landing and taking off in both directions which was a bit confusing. Truscott and Kununurra are in Western Australia, but Truscott works on Darwin time, so I didn't realize it was lunch time in Kununurra when we arrived and the fuel man took a while to come. Luckily he had no problems accepting my few remaining US dollars. It was rather hot so I ditched the left side pannier tank to avoid temperature problems on the climb out; they're more difficult for Miles to lift up than our regular luggage panniers and I thought we'd have enough fuel without it even if it was going to be a very slow flight to Darwin dead into wind. It was very rough as we climbed out of Kununurra. Very early mornings are clearly the time to start flying in Australia. We were heading North East now, but the wind was more south east than north east so the head wind wasn't as bad as I'd feared. While we were bouncing around in some 1000ft / min ups and downs Brisbane came on the radio and started asking complicated questions about whether I wanted to reactivate my SARtime, a time after which Search and Rescue would be activated. I though it had never been deactivated as I'd filed a sort of double flight plan in Truscott with a SARtime which included both flights, but I gave them a new ETA for Darwin which seemed to make them happy, it was nice to know that they were looking out for us. The turbulence settled down a bit as we got to the coast but even over the sea it was still fairly bumpy in the offshore wind. They'd said at Truscott that it was a nice flight up the coast, and they were right, it was a very nice coast with a lot of long white sandy beaches, completely deserted apart from the occasional Aboriginal community, some of which had airstrips. The tide was out so usually plenty of places to land. They have massive 7 metres tides here, so there was a lot of mud and sand streaming out of the many river estuaries. I'm sure I saw some salties in an estuarine lagoon, but in truth we were too high to be sure. We'd crossed from Kupang to Truscott at an average speed of only 46 Kts. At 56 Kts it was a bit faster to Kununurra and the last leg up to Darwin at 57 Kts was faster still, so Darwin came into sight sooner than I'd expected. That forecaster I'd spoken to in Kupang was right, there was lighter winds today than yesterday. I still don't think we'd have made it direct though. The press were waiting as we taxied into Darwin airport. So were Customs, Immigration and Quarantine. The Quarantine man took one look and decided the machine didn't need to be sprayed; "all the bugs would have blown off" was his conclusion. Without either of us being able to say a thing to the press we were marched into the terminal building to do paperwork. Immigration was pretty easy, the chap was aware where we'd come from as the press had been hassling them all day to get out onto the airport to cover our arrival and Bagus had done a good job of our General Declarations and other paperwork. Customs are obviously the big cheeses in Australia however, and our man in Darwin clearly had ambitions to be chief inquisitor. Despite the fact we had no luggage he could search for weapons, drugs, peanuts Etc. he had all sorts of problems. "Where have you come from?" We told him, and that we'd telephoned from Kupang and Truscott and Jon Cook had from Darwin. "But you didn't say you were going to Kununurra". We didn't know until last night, I said, but the wind was too strong to come direct and it was in our flight plan. "But it's a fruit growing area and you could have left bugs there!" he said, triumphantly. The quarantine man rolled his eyes in a way which said 'what planet are you on?' "You're flying a foreign aircraft and Interpol has to be informed" was his final shot; "I need to know your exact route across Australia." Thinking that the press were obviously very interested in us and his best bet would be to read the newspapers, the only thing I could say was "I don't know, I haven't got any maps yet!" We were let out just in time for the evening news in Sydney with the promise that we'd let him know our route as soon as we knew it. Quite why Interpol would be interested in our progress I can't really imagine. I can imagine a man in an office in Lyon getting a fax, and saying to himself in French 'nonsense from that man in Darwin again' and scrumpling it up and tossing it into the bin. The chaps in Truscott had phoned ahead to see if there might be space in their hangar in Darwin, there was. We taxied round there in the growing darkness. While we were waiting for Peter Lymn, CHC's base manager in Darwin to open the doors I had a vision of the only decoration in my room at Truscott, a big sticker which said "SARtime cancelled?". I radioed ATC just to make sure it had been, and it had; it would have been very embarrassing if a search had been started while we were testing out cold beers in the hotel. |